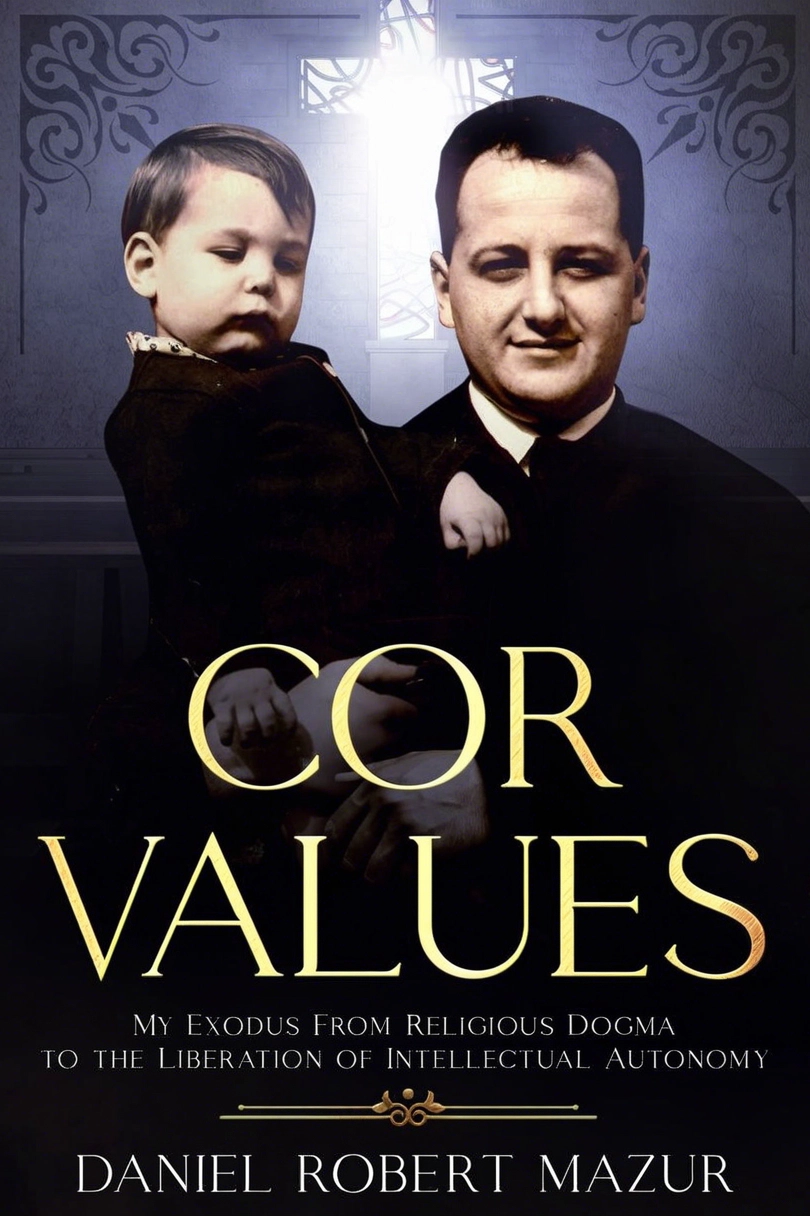

COR Values - A Story of Faith and Family

Intricate Journey of a Man

“COR Values” unfolds the intricate journey of a man, the son of a pastor, who faces familial estrangement due to his atheistic beliefs. The narrative deeply examines his efforts to find common ground between his own convictions and his family’s faith, touching on broad themes of acceptance, identity, and the innate desire for familial bonds.

The story is notably rich in detailing the main character’s battles, both within himself and with his family, extending the conversation beyond simple religious disagreement to encompass wider issues of acceptance and personal identity. This careful portrayal brings to light the complexity of his challenges, making the narrative emotionally compelling and widely relatable.

The book’s exploration of the tensions between personal beliefs and family dynamics, the journey towards acceptance, and the pursuit of understanding and reconciliation is executed with skill. Through detailed storytelling and comprehensive character exploration, the author prompts readers to ponder their own family ties and belief systems.

“COR Values” is particularly poignant for its deep dive into the themes of faith, family, and forgiveness. It is a recommended read for those navigating the tricky waters of family estrangement, especially when differing beliefs are at play. The narrative offers valuable insights into empathy, dialogue, and understanding as tools for healing rifts.

In summary, “COR Values” presents a compelling narrative for readers interested in stories of familial discord and the quest for reconciliation. Its thoughtful examination of these themes provides meaningful lessons on personal and familial growth, making it a significant contribution to discussions around faith, family, and the power of forgiveness. MORE

website maintained by ComputerITSolutions.net

website maintained by ComputerITSolutions.net